深度学习科研最佳实践:我的做法

Published:

思考和总结了科研工程方面的习惯和经验。

Inspired by Karpathy’s impressive post A Recipe for Training Neural Networks, I decided to review and share my daily route of engineering works on Machine Learning related research. Compared to Karpathy’s advice, I’d like to talk more about approaches or practices instead of strategies. This article is merely a personal revision from a newbie, so any suggestions are welcomed.

The Philosophy

Everything is a file.

– one of defining features of Unix

I believe that it is extremely important to learn from failures, before which recording and observing may be the first step. So I’m obsessed with store and organize everything for future review.

Dataset+

I added a plus symbol to emphasize the difference between the original dataset and experiment-usable dataset. From my point of view, a dataset+ may include the following parts:

- raw images and label file provided by the authors

- an explore script/notebook to view images and labels

- a README file which contains info about the dataset: image numbers, image shape, etc

- a toy dataset whose folder structure is exactly the same as original dataset for running toy example and debug quickly

- framework-specific formats for fast I/O during training:

tf.record,.lmdb, etc - several list file which contains image names and absolute path of image file

Environment

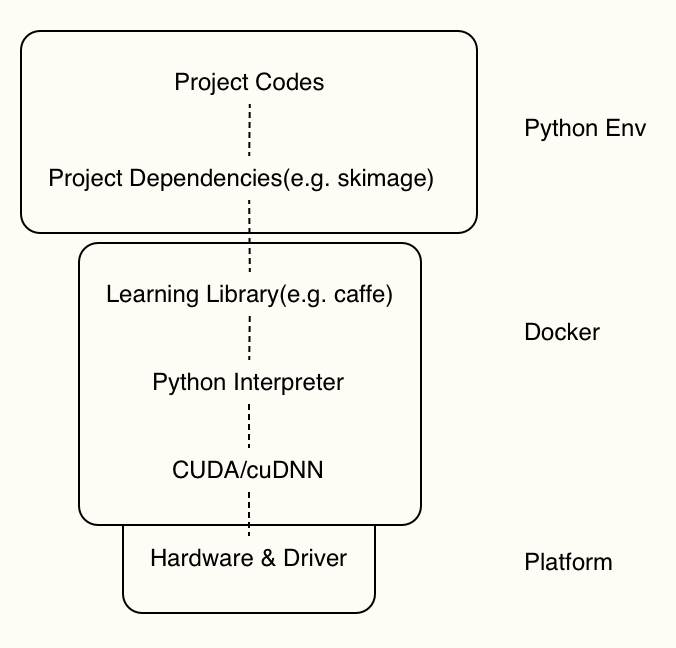

Because of a) the complicated and unstable optimization process b) fast-developing frameworks c) data dependency, the reproduction problem is one of bad reputations of learning-based methods. For a proposed learning-based model, not only the algorithms described in paper, but also its entire reproduction stack as well as the datasets should be taken notice of.

Thanks to container technology and Python environment management tools, namely Docker and virtualenv etc, we’ve got much more control on the environment where our codes run. I prepared two Dockerfiles, one of which is for development and another for production (release). Upon docker images, a virtual env will be created for each project. A lot of tools is useful for environment management in Python, including conda-env, pyenv, peotry, pipenv, or just a requirements.txt file.

Every time running an experiment, a docker container will be built and only projects dependencies are installed, which both can be totally controlled through Dockerfile and requirements.txt (or equivalents).

Experiment Management

Codes

All codes are monitored using git, with at least one commit per day if any files changed. I once suffered a lot from a unintentional bug which can be found immediately if I used VCS in my early days. I encourage myself to only write codes which can be released.

Configs

Configs mainly include hyper-parameters of an experiment. Common items are: dataset root directory, output directory, checkpoints directory, learning rate, batch size, GPU ids, epochs, input shapes, loss weight, etc. I think that a perfect configure system should be:

- Serialized. The configs should be reusable across time and machines.

- Readable. Easy to understand for human(both authors and others).

Current options:

- shell script/command line +

argparse: easy to implement, need extra effort to manage scripts. e.g. SPADE - YAML files +

configvariable: require utility functions to parse YAML files and updateconfig. e.g. StackGAN-v2 - Python

dict: easy to implement, but add unnecessary code pieces. e.g. mmdetection - Google’s Gin: similar to YAML files, require

ginpackage. e.g. compare_gan

Checkpoints, Logs and Visualization

I used to create a checkpoint folder under my home directory and organize checkpoints based on projects and datasets. On the other hand, a model folder is created for pretrained models and released models. They are usually shared across projects. Inside projects, different runs are identified with starting time.

Logs are stored in the corresponding checkpoint folder during training, with stack version, hyper-params, train loss per batch and val loss per epoch recorded. I also store middle results in a separate folder for debug. Some scripts for parsing logs are required.

Tools like Tensorboard and Visdom are useful for visualizing loss changes on the fly during training. Furthermore, they can basically record nearly everything. However, they usually need additional ports and eat memory. It’s recommended to mount the log folder and then run these visualization tools on another machine.

Outputs

The output folder is where I store predicted images, numpy arrays, and text files for evaluation (validation set) or submission (test set). In this way, the evaluation process can be decoupled from the training process, and it’s rather suitable when comparing different methods (or models from different runs).

Misc

Playground

The playground refers to a super environment for trying new codes, packages or getting familiar with some functions. It can also be a single jupyter notebook inside the project folder.

Jobs and Scripts

Shell scripts to bundle a series works for an environment, e.g. a preprocessing-training-evaluation-visualization-test pipeline.

Debug Folder

Debug folder stores anything provide insights from debugging process. It also serves as a transfer station between training nodes and my personal computer.

Inline Notes

I often writing notes as comments inside codes and git comments. They will be reorganized to note-taking apps during the review process.

Final Thoughts

I hope that creativity is the only constraint of my research, not engineering. Thanks for your time and feel free to leave your advice below.